(from Latin rudis = "rough" or "raw," or from rudus = rubble, crushed stone) are an extinct group of marine bivalves that could develop some very fascinating and bizarre shell shapes. They lived between 150 and 65 million years ago during the Mesozoic Era, the time when dinosaurs dominated the land. Their fossils can be found throughout the Mediterranean, Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, Central America, and the Middle East.

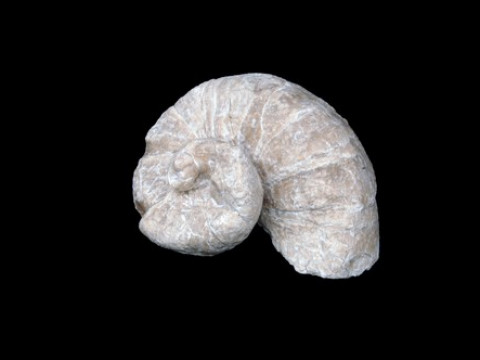

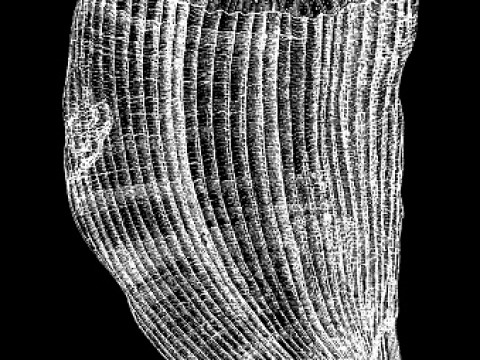

Rudists lived a sedentary lifestyle, attached to the seafloor or a solid object like a shell fragment. They were suspension feeders, filtering seawater in search of plankton and other nutrients. Unlike modern bivalves, such as mussels or oysters, which typically have two similarly sized and shaped shells, rudists were different. Their defining morphological feature was having two thick, asymmetrical shells of unequal size—one larger and more robust shell typically anchored them to the substrate or a neighboring rudist, while the smaller, upper shell served as a lid to protect the organism's soft tissue. Rudists grew by fusing with each other, forming reefs. Larger formations of rudists could live longer and reproduce more frequently, which is why their fossils are often found in large communities of multiple individuals, rarely as solitary specimens. Their shells are usually preserved in the same position they occupied during life. Early primitive rudists had elongated, tube-shaped shells, while later Cretaceous rudists resembled inverted cones. These shapes varied significantly in size, from just a few centimeters to over 1 meter in length, making some rudist species among the largest known bivalves.

Rudists first appeared in the Late Jurassic, between 150 and 160 million years ago, but truly flourished during the Cretaceous Period, experiencing several phases of rapid development as well as mass extinctions. Although modern tropical reef ecosystems are simply referred to as coral reefs (in homage to today's main reef-builders), reefs in the past were not always constructed by corals. The first reefs appeared in the early Paleozoic, while in the subsequent Mesozoic, rudists became the primary reef-building organisms in tropical seas, the first mollusks to achieve this role. Such communities could grow quite large—some fossil rudist reefs stretch for hundreds of kilometers. These reef structures could withstand normal wave impacts but were destroyed by hurricanes and major storms. Rudists frequently regrouped after such events, sometimes building on rubble that had tumbled down steep reef slopes, creating formations hundreds of meters high. These thick, porous accumulations of broken rudist debris later became valuable oil reservoirs in the Gulf of Mexico and the Middle East. Rudists built their durable homes by extracting calcium and bicarbonate from seawater, depositing multilayered shells made of calcium carbonate. In colder seas further from the equator, rudists shared their habitats with scleractinian corals, which continue to build reefs today.

Towards the end of the Cretaceous, rudists became increasingly dominant, replacing corals in many areas before their eventual extinction. The Cretaceous Period was characterized by higher global temperatures than today—on average, 6 to 14 °C warmer, with shallow seawater temperatures in rudist habitats exceeding 32 °C. Their evolutionary peaks and declines were linked to environmental changes, including sea temperatures, sea levels, salinity, nutrient availability, and sediment influx. Paleontological research has shown that rudists in Central America and the Caribbean went extinct a million years earlier than those in the Mediterranean and further east, where they survived until the very end of the Cretaceous. Their extinction coincided with the uplift of land and the formation of mountain chains, which destroyed marine habitats. Generally, sedimentary records indicate that rudists were closely associated with former carbonate platforms—large, expansive, relatively shallow marine areas marked by the deposition of carbonate sedimentary rocks such as limestones. For example, the rocks on the Brijuni Islands were deposited on the former Adriatic Carbonate Platform, remnants of which now form most of Croatia's coastline and islands. Many modern islands along Croatia's coast are built from rudist limestones, such as Cres and Brač (the famous construction and architectural Brač stone containts rudists fossils).

Beautiful examples of rudist limestones can be seen on the island of Veli Brijun at outcrops near Cape Turanj, on the Zelenikovac Peninsula, and also on Pusti Otok (Madona). Although rudist limestones in Croatia are mostly associated with Upper Cretaceous deposits, they appear earlier in the Lower Cretaceous on Brijuni. On the Zelenikovac Peninsula and Pusti Otok, one can find fossilized accumulations of rudists and other marine organisms, forming small, isolated reefs known as "patch reefs."

Parks of Croatia

Parks of Croatia

EU projects

EU projects English

English